by Stephen B. Presser

The indispensable Victor Davis Hanson recently noted, “Real coups against democracies rarely are pulled off by jack-booted thugs in sunglasses or fanatical mobs storming the presidential palace. More often, they are the insidious work of supercilious bureaucrats, bought intellectuals, toady journalists, and political activists who falsely project that their target might at some future date do precisely what they are currently planning and doing—and that they are noble patriots, risking their lives, careers, and reputations for all of us, and thus must strike first.”

He was discussing what we are now beginning to understand was the attempt to oust Donald Trump begun by officials in the Obama Administration, including certainly former FBI Director James Comey, assistant director Andrew McCabe, former acting Attorney General Sally Yates, former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, former CIA Director John Brennan, former FBI counterintelligence chief Peter Strzok, former FBI attorney Lisa Page, and quite possibly President Obama himself.

This will, in the long light of history, be regarded as the greatest misuse of governmental power ever to appear in our politics, and yet there has been very little attention paid to how this could occur and why at this particular time in our political development.

Equal Protection Denied?

To a hammer everything looks like a nail, and to a law professor like me, everything looks like a problem in jurisprudence, and it does appear that it was a change in our approach to law in the courts and the law schools in the middle of the twentieth century that is responsible for the betrayal of our democratic ideals on the part of those who attempted the failed coup against Donald Trump.

It is, of course, always characteristic of those in power to believe they ought to stay in power, and to them any means at hand are justified by that end. Perhaps this is the simple answer to why these miscreants did what they did, but I think the problem is a deeper one peculiar to American law about 70 years ago.

At that time a number of American intellectuals began seriously to question the existing laws, particularly in the Southern United States, that seemed wrongly to be subjugating African Americans (the Jim Crow laws), and, in the name of equality, they embarked on an intellectual project suggesting that the courts could remove these vestiges of slavery through an expansive interpretation of the 14th Amendment, which provided that no state should deny to any of its citizens “the equal protection of the laws.”

The research of the distinguished legal historian Raoul Berger made clear in the 1970s that the historical meaning of the phrase “equal protection” was simply a guarantee that no citizen could be denied access to the courts to uphold property and contract rights, but that historical understanding certainly did not reflect a clear wish to give federal courts power to reallocate the responsibilities of state and federal governments that were clearly provided in the Constitution. After all, the 10th Amendment makes clear that the federal government (including the federal courts) is to be one of limited and enumerated powers, with the governments closest to the people—the state and local bodies—given whatever residue of power existed, save that which was retained by the people themselves.

Judges Reign

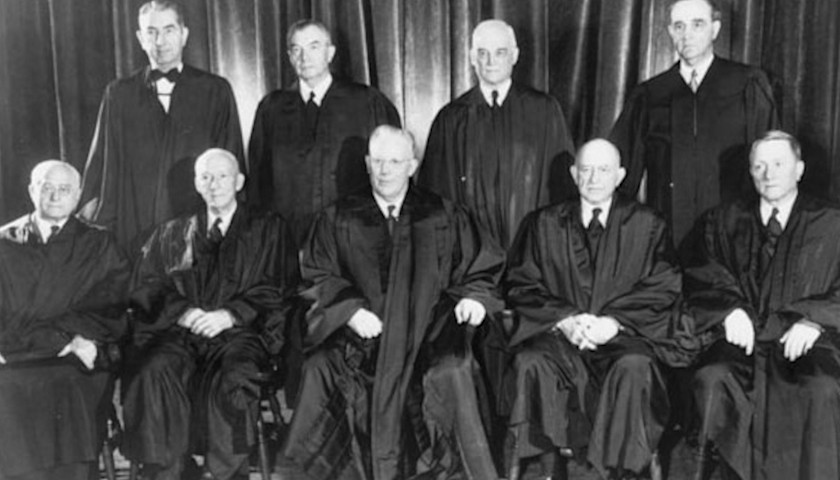

Berger called the book in which he made this case Government by Judiciary, to emphasize that from the 1950s to the 1970s, and, in particular, the work of the Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the most important policy-setting organs in the republic became the federal courts, rather than Congress or the president.

Our courts are still making policy, particularly as a brace of Obama-appointed judges seek to nullify executive initiatives of the Trump Administration, but it was the attitude of the Warren Court justices and their acolytes on the lower courts and in the academy that are of most interest to us here.

As one of them, a United States Court of Appeals judge, J. Skelly Wright, made clear in an important 1971 Harvard Law Review article, what the Warren Court was doing was implementing a jurisprudence of “goodness,” to redress then-existing evils such as racial segregation, legislative reapportionment that favored rural over urban districts, purportedly unfair investigative techniques resulting occasionally in coerced confessions, and, he might have added, mandated prayers and Bible reading in the public schools.

All of these things were clearly matters traditionally left to the discretion of the states, but the Warren Court proceeded to rewrite the Constitution to remove that discretion. Thus our pluralistic society became more centralized, and as a result a cadre of enlightened ephors in Washington decided they possessed superior wisdom to the rubes in the hinterlands.

The Warren Court never described the state legislators whose authority they supplanted as “deplorables,” as Hillary Clinton would notoriously label President Trump’s supporters, but the sentiment, sadly, was probably the same.

While it is undeniable that there was some nobility in what the Warren Court did, that nobility was in the service of undemocratic means, as the popular sovereignty on which the Constitution ultimately depends was dangerously eroded by that court.

It is equally notorious that something similar happened with decisions of the Burger Court such as Roe v. Wade, or decisions of the Roberts Court such as NFIB v. Sebelius or Obergefell v. Hodges. These were all cases where a majority of the Supreme Court decided to overrule policy decisions appropriately made by state governments, in the service of a purportedly superior ideology professed by particular justices.

It is no coincidence that deep state bureaucrats such as Comey, Brennan, Clapper, et. al., and the Harvard Law School-trained Obama would be tempted to act on what they must have seen as their superior judgment to the voters of flyover country who chose to elect Donald Trump. To these federal officials, the Fabian socialist policies of the Obama Administration, purportedly dedicated as they were to equality, efficiency, redistribution, and centralized control were the inevitable wave of the future, and nothing as trivial and outdated as the Electoral College (or perhaps the Constitution itself) ought to be permitted to interfere.

What Justice Requires Now

If we are still a republic governed by the rule of law, then those who engineered this failed coup (to use Hanson’s and Roger Kimball’s term), with its Russian collusion scheme must be brought to justice, and there is every indication that Attorney General Barr understands this and is proceeding accordingly.

Equally important, however, is that we understand the poisonous nature of a legal philosophy that enables justices, judges, and even bureaucrats to overrule the decisions of state and federal legislatures or voters not because they have exceeded traditional and historical constitutional limits, but because those decisions are not in keeping with the tenets of progressive ideology.

Donald Trump and William Barr have their work cut out for them in rooting out the excrescences of an overweening federal leviathan, and Trump’s appointments to the federal bench should be instrumental in that effort, as well.

It is now time, however, for our law schools, enamored as they have been with the Warren Court and with judicial policymaking, to come to an understanding that a return to more traditional notions of jurisprudence and constitutional hermeneutics are essential. If the rule of law and popular sovereignty are to remain as the cornerstones of our polity and our Constitution—the real appeal of Donald Trump to his supporters, and the two quintessential aspects of American greatness—this simply is indispensable.

– – –

Stephen B. Presser is the Raoul Berger Professor of Legal History Emeritus at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law, and the author of “Law Professors: Three Centuries of Shaping American Law” (West Academic Publishers, 2017). This year, Professor Presser is a Visiting Scholar in Conservative Thought and Policy at the University of Colorado, Boulder.